How to Read a Cannabis Patent

How to Read a Cannabis Patent

Previous posts have discussed cannabis patents, here, and here, and here. Today I explain the basics of how to read a patent. Why would you want to do such a thing? If you are in the cannabis business, you may own a patent, or be threatened of infringing one. The tips below will give you a good start on understanding what a patent means.

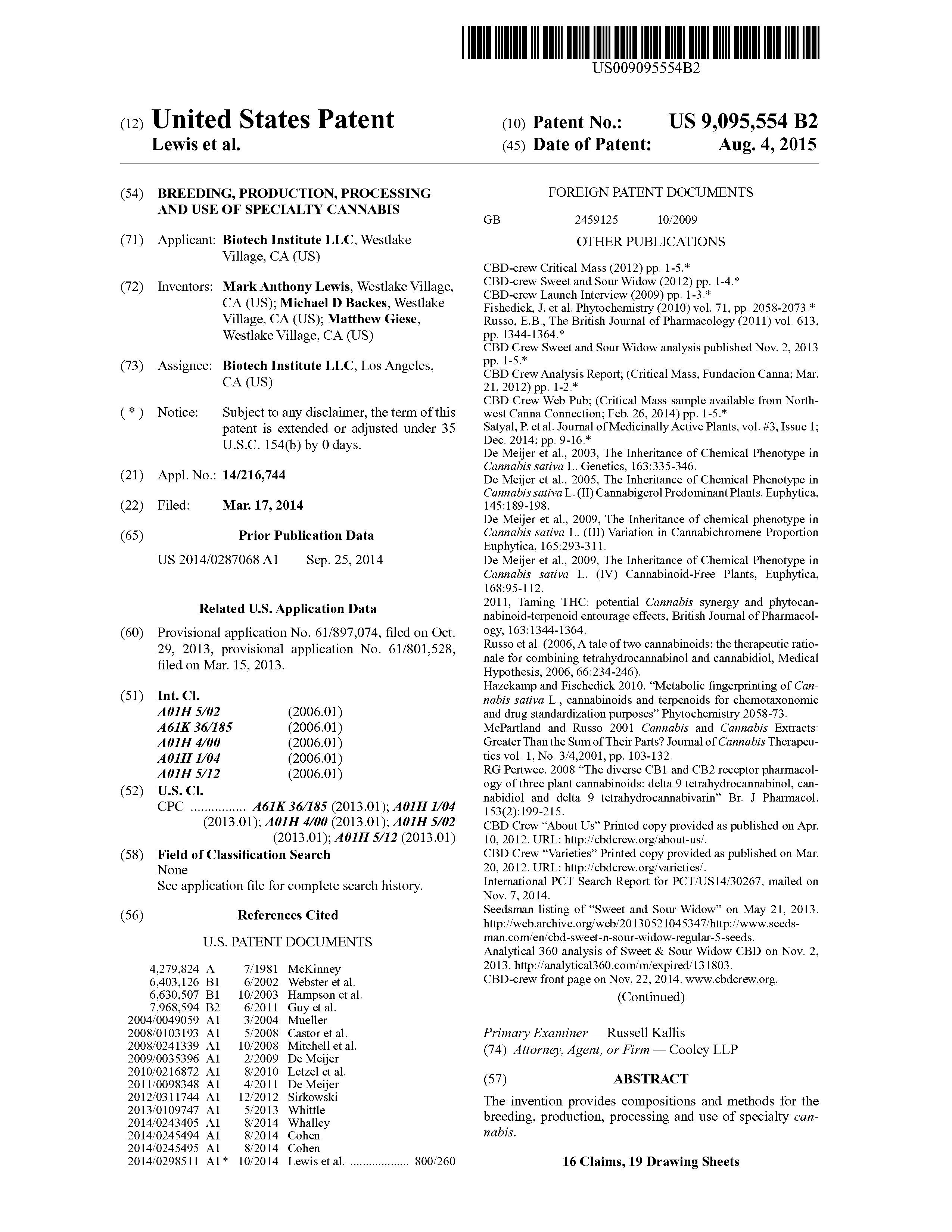

Today I focus on utility patents, which are about 90% of all patents. (The other major category is design patents.) Utility patents can cover such things as cannabis plants, or methods of making cannabis plants. Utility patents have four basic parts: introductory material, drawings, the specification, and the claims. To read and understand a patent, you should be be familiar with each of them.Unsurprisingly, the introductory material is at the beginning of the patent (shown above). It starts out with the patent number, the date the patent was issued, the inventor(s), and the assignee — if there is one. It also provides the filing date of the patent, which is usually several years before the issue date. The next important part is the “references cited,” a list of prior art that the patent examiner looked at. There is also a short “abstract,” a sort of summary of the invention, often followed one or two pictures of the invention. While the abstract and the opening pictures can give a good idea of what is to come, they do not define the invention. More on that later.

Next are a series of stylized line drawings or charts. While making patent figures is an art, the figures are not intended to be artistic. Rather, they are there to help the reader understand what the invention is, and perhaps how it is used. Like the abstract, the figures do not define the invention. In fact, some of the figures may not refer to the invention at all.

Following the figures is one or more pages of text in 8 point type, set out in two columns separated by a narrow column of numbers. This is generally referred to as the “specification,” or “spec” (although technically the specification also includes the figures and the claims). The specification usually gives the background of the invention, a summary of the invention, often a brief description of the drawings, and then a “detailed description of the invention.” This sets out the nitty gritty technical details of the patent, usually making reference to the various drawings by number. Although the specification gives this detailed description, once again, it does not define the invention.

Finally, tucked away at the very back of the patent, shyly hiding behind the specification, are one or more patent claims. The claims are numbered, and always start with “What is claimed” or “I claim” or “we claim” or similar language. What, you may ask, do these puny claims do? Well, they define what has been invented, that is, what is covered by the patent. They are the equivalent of the deed to your house, which describes, in somewhat technical terms, exactly where your property begins and ends.

So how do you make sense of all of this? I suggest that you start with the introductory material. Then turn to the claims. Keep in mind that in order to infringe a patent claim, whatever is accused of infringing must have every single thing listed in the claims. If the claim is for a hybrid cannabis plant, which produces a female flower comprising CBD content of >3% and a terpene profile of alpha phellandrene, a plant that has only 2% CBD won’t infringe.

Next, look at the drawings and the specification. I usually print out an extra copy of the drawings and have them open when I read them. Once you have done that, you can go back to the claims with a better understanding. Often, claims only contain part of what is in the specification. But the claims are the key to knowing what the patent is about.

Most importantly, have fun! You could be reading the tax code.

Go to Source

Powered by WPeMatico